A different way to look at grain boundaries in polycrystals

December 11, 2025

In fine-grained metals, the usual plastic deformation is replaced by new mechanisms involving the interfaces between crystalline domains, known as grain boundaries. In a recent study, researchers observed for the first time, on the scale of a large set of grains in aluminium, the coupling between the movement of the boundaries and the macroscopic deformation of the metal.

As crystalline materials, metals are composed of crystalline domains separated by interfaces, known as grain boundaries. In most cases, plastic deformation of metals involves the nucleation and propagation of nanometric linear defects, known as dislocations, within the grains in order to prevent fracture. Over the past twenty years, with the advent of materials with very small grains (on the order of microns and below), new plasticity mechanisms have been discovered. Due to the difficulty of creating dislocations, plasticity develops in these materials preferentially at grain boundaries, in particular through a mechanism coupling deformation and boundary migration. Although this mechanism has been described both experimentally and theoretically at the interface scale, its importance at the collective scale of a large number of grains was still poorly documented.

To achieve a relevant description of this scale, an international team led by CEMES in Toulouse combined mechanical tests at different temperatures, deformation measurements and maps showing the displacement of grain boundaries in ultra-fine-grained aluminium. These measurements are based in particular on observations using both atomic force microscopy and electron microscopy. They show that the deformation caused by the movement of boundaries occurs predominantly, regardless of the nature of the interface, but is much less effective than theoretical models predicted. These models rarely considered the presence of specific defects, called disconnections, which move along the boundaries. However, experimental observations suggest that these disconnections are more varied than expected and probably operate in concert with high-temperature diffusion, contrary to what was previously assumed.

This work could explain certain post-heat treatment deformations in industrial parts and thus remedy these production defects in metals and alloys. Above all, it allows us to change our perspective on grain boundaries in metals, which should no longer be considered as elementary defects, but as specific crystal lattices, carrying their own defects, which in turn influence the behaviour of the boundary.

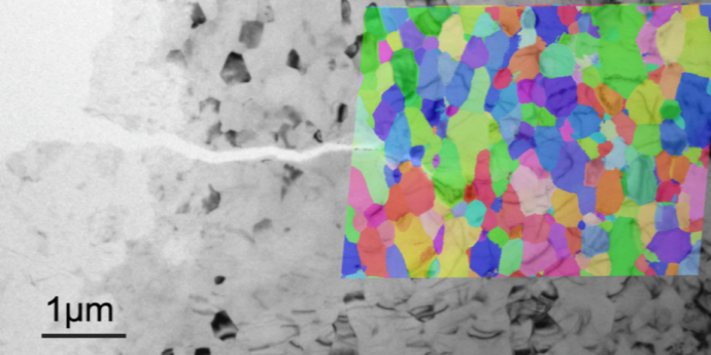

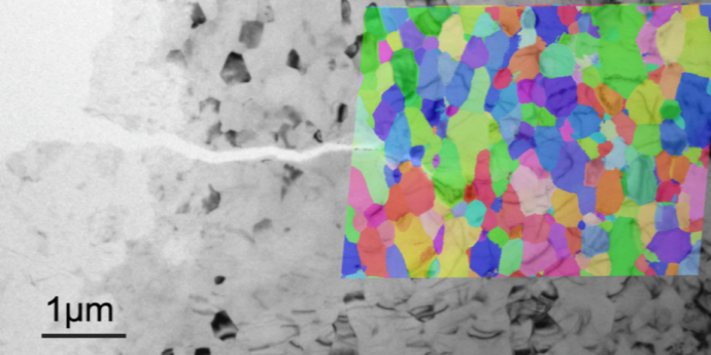

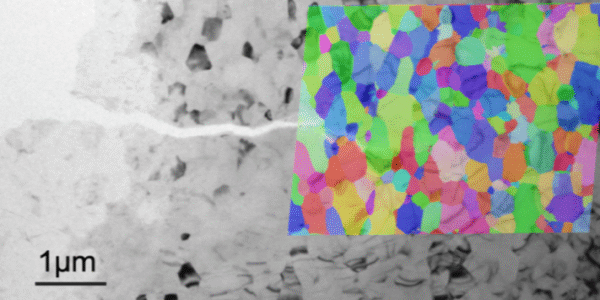

Ultra-fine grain aluminium observed under transmission electron microscopy showing a crack propagating in an area where all crystal domains with different orientations (the ‘grains’) are identified by colour. As they move, the interfaces between these domains (the ‘grain boundaries’) carry a small deformation that can blunt the crack.

Ultra-fine grain aluminium observed under transmission electron microscopy showing a crack propagating in an area where all crystal domains with different orientations (the ‘grains’) are identified by colour. As they move, the interfaces between these domains (the ‘grain boundaries’) carry a small deformation that can blunt the crack.

Contact:

Marc Legros | marc.legros[at]cemes.fr

Frédéric Mompiou | frederic.mompiou[at]cemes.fr

Publication:

Quantifying grain boundary deformation mechanisms in small-grained metals

R. Gautier, F. Mompiou, O. Renk, C. Coupeau, N. Combe, G. Seine, and M. Legros

Nature, 648, pages 327–332 (2025)

DOI: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09800-7